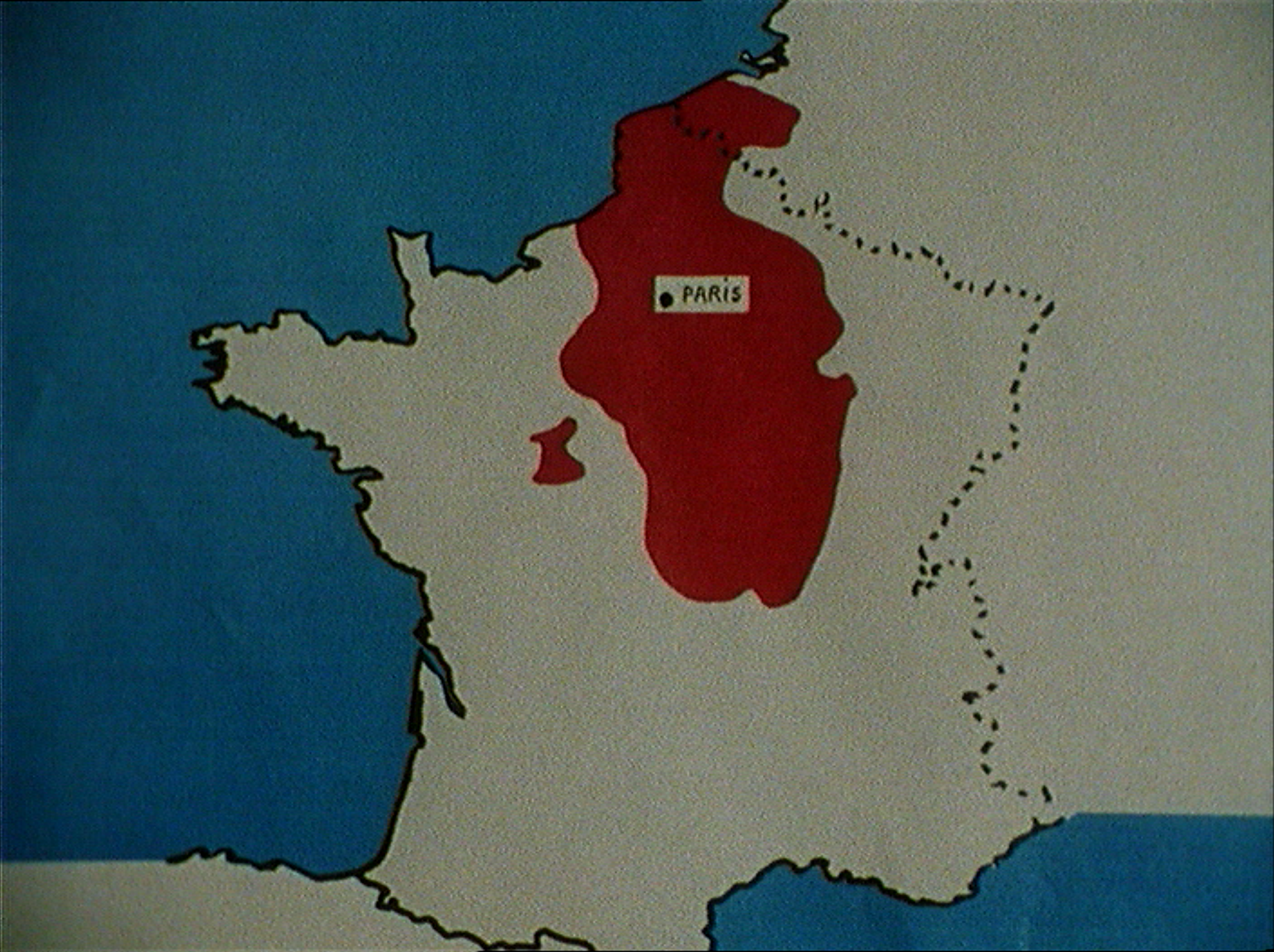

Mapping (with) Moullet

From Terres noires (1961) to Toujours moins (2010), Luc Moullet’s short films have often served as grounds for mapping and inventory, either portraying overlooked localities […]

Read More

Rocío: The Heavy Burden of the Continuity of Power

Top: Still from Rocío (Fernando Ruiz Vergara, 1980) showing the Pentecost Mass during the El Rocío pilgrimage in 1977.

Bottom: Still from a Canal Sur Televisión news broadcast showing the Pentecost Mass during the El Rocío pilgrimage in 2024.

The image on the left is composed of stills from two recordings made in the same space at distant points in time, which seem to merge in a strange specular game. The upper one is from the film Rocío (Fernando Ruiz Vergara, 1980) and was taken in 1977 at one of the masses celebrated during Andalusia’s famous Marian pilgrimage of the same name. In the film, the bishop officiates, surrounded by priests and devotees in front of an audience, sleepy after a long night of celebration and feasting. We could have chosen many other stills from the film, some of which have rarely been shown to the Spanish public during the last four decades.

Read More

Images of Land Struggle

Top: Still from Fertile Memory (Michel Khleifi, 1981).

Bottom: Still from Nuestra Voz de Tierra, Memoria y Futuro (Marta Rodríguez and Jorge Silva, 1981).

This is an attempt to juxtapose two sequences from two films produced around the same period in 1981 but set in different geographies. Both present a relationship with land that resists settler colonialism, thereby redefining fixed property relations. In both scenes, the body is central to the refusal of the land dispossession, whether through an active reappropriation or a refusal to sell, swap, or enter into a transactional relation that would lead to the symbolic loss of the land.

Read More

Fragments on the Paranational Dynamics of Cinema

1/8 [Brigitta Kuster *]

At home, with oneself – that would be the site, this geographical space: a city, a village, a region, a nation state, sealed, fortified. This has actually never been the case. In fact, in the modern age, fixation and sedentarism became a compulsion, an ideology and a myth, which was supposed to bring mobilisation under control. The historical emergence of film and cinema, in particular, has brought to the fore the paradigm of the journey, the route, the passage to be travelled or the distance to be bridged, which is not only induced by the motion of machines. Moving images. And this conjuncture has certainly not hindered the development of cinema as a business. What has been a challenge to film theory, however, is the fact that with film, we are always already heading somewhere else. Easily carried away and therefore difficult to grasp, we are completely with or even within ourselves and yet somewhere else, at the same time ici et ailleurs.

Read More

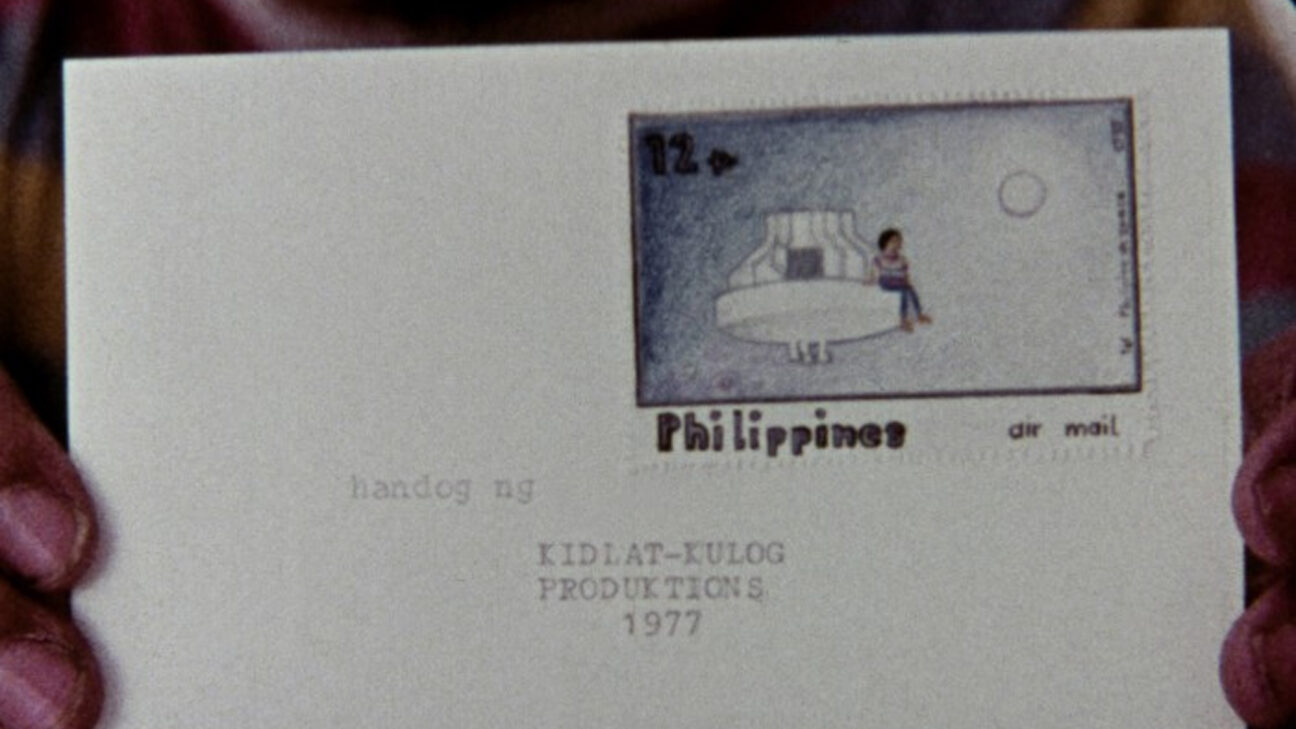

‘Paranational’ Instances in Cinema: Modes, Methods and Conditions

Mababangong Bangungot [Perfumed Nightmare, Kidlat Tahimik, 1976]. Film still. Kidlat Kulog Productions. Source: International Film Festival Rotterdam.

The very title of this research project and the summary of its theoretical and methodological aspirations entail a rather paradoxical and productive nexus. Should the efforts to look beyond the label ‘national cinema’ be pursued under a designation (‘paranational cinema’) with a similar overarching tone? To avoid precisely this pitfall, one should prefer to speak of ‘paranational in cinema.’ ‘Paranational’ ought not to be an all-encompassing term: instead of subsuming or overshadowing through homogenization, ‘paranational’ emerges, transpires, and occurs ‘from the bottom up.’ These efforts should thus be concentrated not on imposing definitions ‘from above,’ but on recognizing ‘paranational’ instances in cinema and on bringing them to the surface, through informed observation, meticulous description, and/or contextualized analysis. The unsystematic nature of these occurrences does call for a fairly fluid framework, yet such a framework could run the risk of being too vague. Initial points of reference – which will be detailed below – seem necessary for an in-depth exploration of these matters.

Read More

On the Function of the Term ‘Paranational’

The prefix ‘para-’ comes from the Ancient Greek παρά (pará, “beside; next to, near, from; against, contrary to”). Its meaning in English encompasses, among others: parallel (beside, alongside), adjacent to, opposite of, across, beyond, unrecognized, unsanctioned, avoidant. In these prepositional and exclusionary functions, ‘para-’ indicates an aberrant relation within a wider normative context. Added to the adjective ‘national,’ ‘para-’ can help to describe and interpret practices, modes of existence, or attitudes which are beside, transversal or in opposition to constituent norms of a nation or a nation-state. These aberrations can be actively chosen or ascribed by external powers. Hence, ‘paranational’ can be used to refer to what is unrecognized or considered digressive within normative criteria and can similarly refer to an active dissensus with these criteria or a non-recognition of nation and nation-state as a concept and a functional reality.

Read More

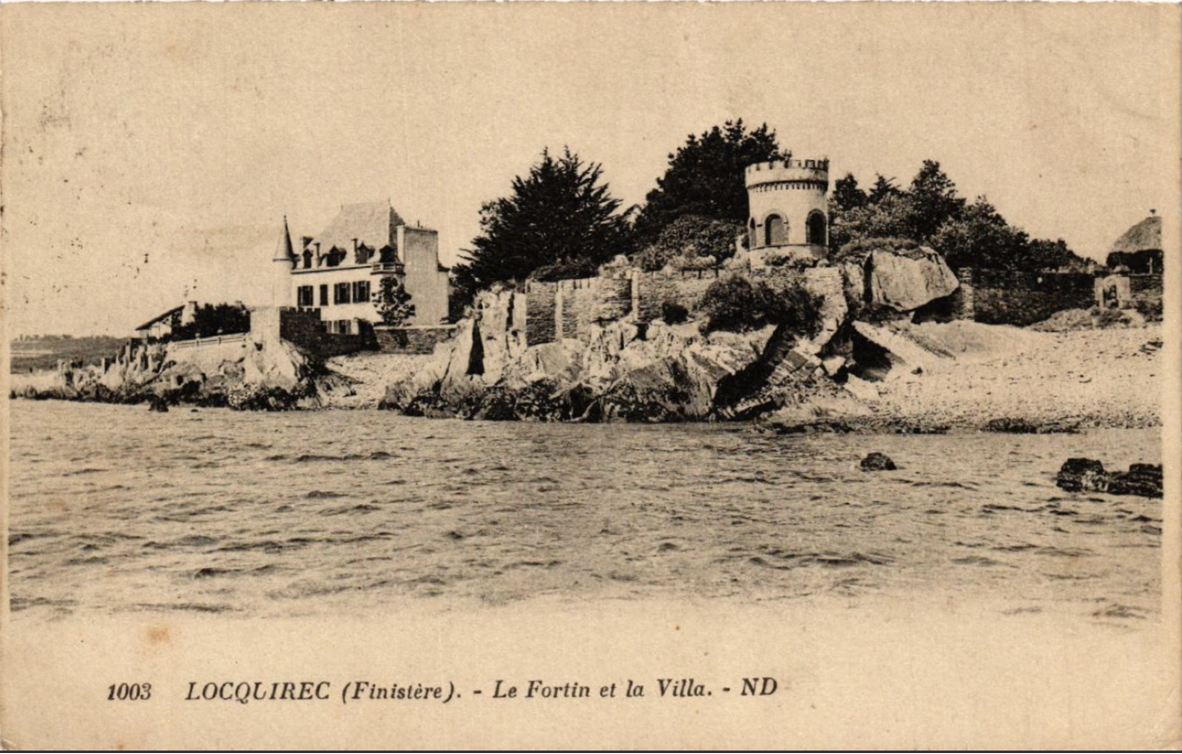

Postcard from Brittany

I imagine that this is how René Vautier might have started a postcard to his friends and colleagues. He was born in 1928 in Camaret-sur-mer, Departement Finistère, Brittany, and he died in Cancale in 2015, also in Brittany. His film Afrique 50, an anti-colonialist manifesto realised in Mali and the Ivory Coast, was confiscated. He had reason to promote himself as the “most censured” French filmmaker. Many of his films side with the Algerian liberation movement.

Read More