‘Paranational’ Instances in Cinema: Modes, Methods and Conditions

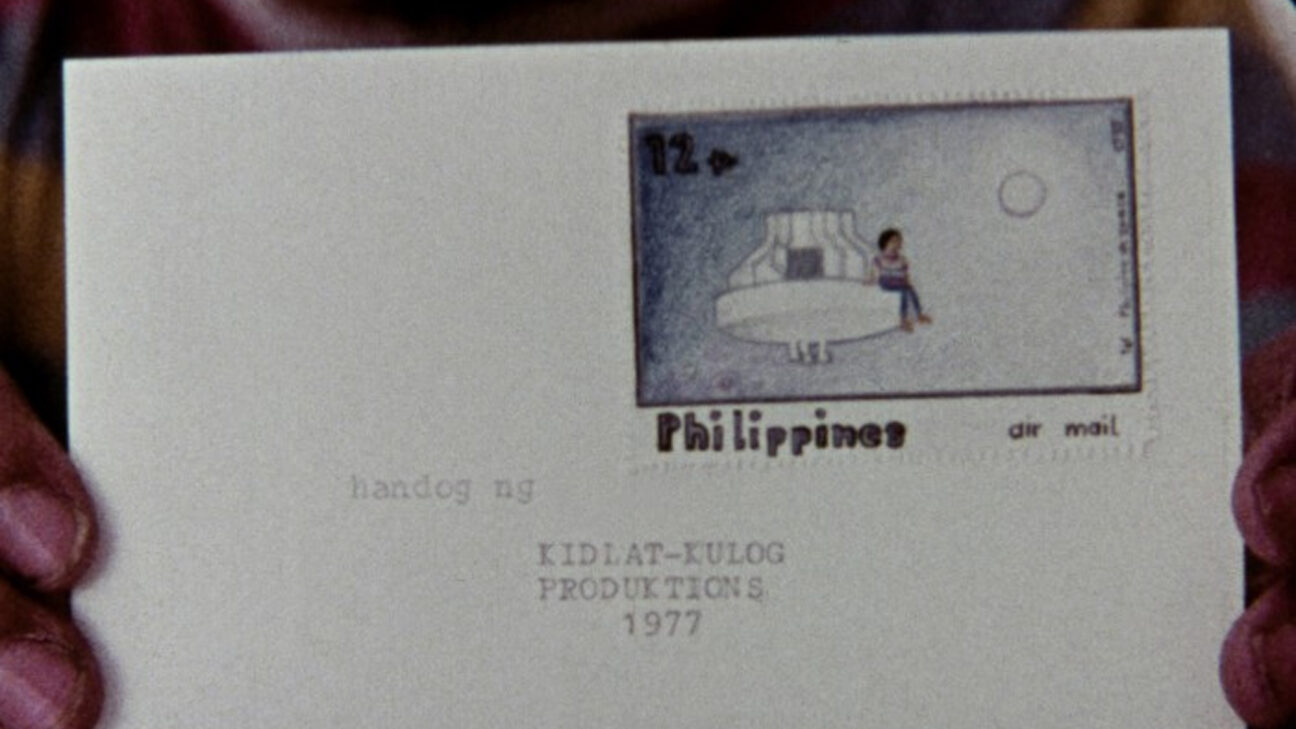

Mababangong Bangungot [Perfumed Nightmare, Kidlat Tahimik, 1976]. Film still. Kidlat Kulog Productions. Source: International Film Festival Rotterdam.

The very title of this research project and the summary of its theoretical and methodological aspirations entail a rather paradoxical and productive nexus. Should the efforts to look beyond the label ‘national cinema’ be pursued under a designation (‘paranational cinema’) with a similar overarching tone? To avoid precisely this pitfall, one should prefer to speak of ‘paranational in cinema.’ ‘Paranational’ ought not to be an all-encompassing term: instead of subsuming or overshadowing through homogenization, ‘paranational’ emerges, transpires, and occurs ‘from the bottom up.’ These efforts should thus be concentrated not on imposing definitions ‘from above,’ but on recognizing ‘paranational’ instances in cinema and on bringing them to the surface, through informed observation, meticulous description, and/or contextualized analysis. The unsystematic nature of these occurrences does call for a fairly fluid framework, yet such a framework could run the risk of being too vague. Initial points of reference – which will be detailed below – seem necessary for an in-depth exploration of these matters.

‘Paranational’ in cinema can be examined through three main sets of instances – modes, methods and conditions – which, for all their distinctiveness, remain inextricably linked, continuously overlapping, affecting, and altering each other.

Modes is principally concerned with the thematic (topics), ideological (discourse), and aesthetic (style) criteria. Thematically, ‘paranational’ may serve to study those aspects traditionally considered to be constitutive of a nation, such as a language, normative culture, or iconography, especially instances that hint at a destabilized, de-homogenized or deliberately bypassed conception of a uniform and immutable nation. By probing films and practices beyond national criteria, the term ‘paranational’ also defies the transnational, in particular its most visibly ‘constructed’ manifestations (for instance, ‘Europudding’ coproductions or Western notions of what an African cinema is and should be [Murphy 2006]), which arguably function as a sum of neutralized or, conversely, emphasized national or cultural attributes. Ideologically, ‘paranational’ lenses can help to discern a critique of the notion of the nation, its values, myths, defining events, emblems, historical figures and preconceptions about it. In cinema, these discourses may be vehiculated through an overt critique, a parody, a satire or different forms of détournement (Kidlat Tahimik’s Mababangong Bangungot [Perfumed Nightmare, 1976] contains many such instances). Aesthetically, ‘paranational’ seems to be a pertinent device to consider films made in reaction to dominant ‘national’ and/or ‘transnational’ tendencies (such as Cinema Novo countering the traditional Hollywood-inspired cinema in 1950s Brazil).

Beyond thematic concerns, ideological (sub)text and formal features, ‘paranational’ also allows to tackle certain methods of producing, disseminating, and presenting films, but also studying films and concomitant processes, practices and materials. ‘Paranational’ instances are likely to be found in alternative practices that eschew dominant models of production, whether ‘national’ (funding by national film institutes, nationally homogenous film crew…) or ‘transnational’ (European funds, funding by international foundations…). Similarly, the dissemination and the presentation of films can be assessed with the help of ‘paranational,’ most markedly in cases where such practices run parallel to established national distribution circuits (for instance, cinémas art et essai in France) or international institutional networks (e.g. Label Europa Cinemas). Finally, various programming, curatorial, archival, film-critical, film-historical and scholarly endeavours, which – rather than to promote or negate – seek to deconstruct or subvert the national character of films, processes, practices and materials, can also be observed through ‘paranational’ lenses.

The two aforementioned sets of instances are conditioned by a third, namely the historical, cultural, political and economic conditions in which the films are produced, disseminated, curated and received by audiences, the media and at the box office, or studied in academia. Although ‘paranational’ might inspect relatively stable national frameworks, it tends to offer a more relevant perspective on states of instability, crisis and insecurity, most notably on conditions where the nation-state the filmmakers, producers, researchers and commentators operate within is under construction, reconstruction, dissolution or re-composition (e.g. production and promotion of Dans les ruines de Baalbeck, the first talking film produced in Lebanon and today considered to be lost [Widmann 2024]). Furthermore, ‘paranational’ can be equally useful for looking at the cinematic processes occurring outside of nationally homogeneous environments, such as the work of filmmakers in diaspora or exile (some of which have been scrutinized by Laura Marks [2000] and Hamid Naficy [2001,] among others).

These three sets of instances are neither meant to represent a typology, nor should they be examined as strictly autonomous from one another, each of them remaining in constant productive tension with the others. It is at their incessantly reconfigured intersections that one should survey for ‘paranational’ instances in cinema.