Mapping (with) Moullet

From Terres noires (1961) to Toujours moins (2010), Luc Moullet’s short films have often served as grounds for mapping and inventory, either portraying overlooked localities or seeking to exhaust all the aspects of a given subject. The most productive period of such experimentation came in the 1980s and the 1990s, when – confronted with meager funding and the rise of private television – Moullet shifted his focus to the short format.

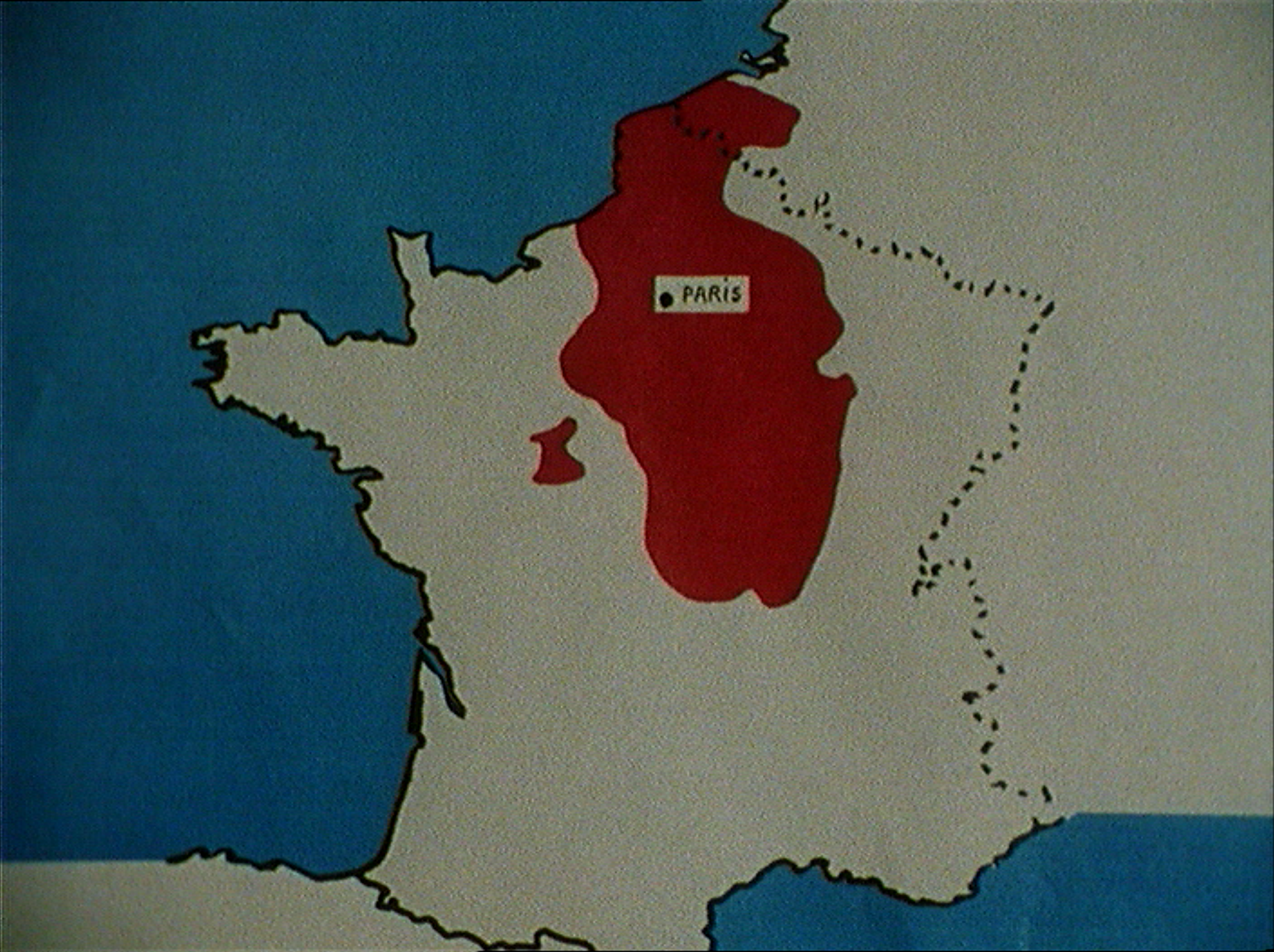

By pointing to paradoxes and inconsistencies, idiosyncrasies and aberrations, Moullet deconstructs ossified institutional structures, chronicles the processes of technological modernization (La valse des médias, 1987), sheds light on late capitalism’s effects, unpacks and parodies both global-capitalist and national emblems. In Essai d’ouverture (1988), he looks for ingenious ways to open a Coca-Cola bottle, as the embodiment of the consumer society, whereas Toujours plus (1994) surveys the supermarkets as “the cathedrals of the future.” In other films, he dissects seemingly trivial, yet far from negligible economic phenomena, such as the dog food and entertainment industries (L’empire de Médor, 1986) or the subway fraud (Barres, 1984). National symbols have also interested Moullet – Paris, the fantasy-ridden city of lights and the center of French political power is seen as “France’s cancer,” and the planting of the French flag in a new capital proves to be as clumsy and burlesque as the author’s entire search for a viable alternative to Paris (Imphy, capitale de la France, 1995). Along the way, Moullet creates an irony-infused geographical and political conundrum, where the national and the transnational intersect with the regional and the local, as he draws parallels between the metropolises such as Paris, Canberra or Brasilia and the unassuming localities of Imphy, Avord, Le Comtal or Aumelas.

Less charted territories are just as prominent in other shorts. Les Havres (1983) depicts the port city of Le Havre as a heterogeneous constellation of districts. La cabale des oursins (1991) humorously advocates for valorizing the spoil tips in the north of France. Foix (1994) is a benign parody of travelogues, a very popular tourist advertising format at the time, through an essayistic scrutiny of contradictions and incongruences of what Moullet designates as “France’s most unfashionable town.” Finally, Le Ventre de l’Amérique (1996) shows the flipside of the cinematic America by taking the viewers into the heart and “belly” of the USA. Far from Hollywood and New York, Iowa is both crucial for the American economy and the birthplace of “the national star” – John Wayne. The various maps, but also globes, drawings and postcards, used in these films not only emulate the travelogue conventions and direct the observer-tourist, but also suggest that such representation – not unlike the attractive travel documentaries he parodies – smoothes out the phenomenological, aesthetic and infrastructural unevenness of places. Or, as Tom Conley (2007, 2) put it some years later: “Both maps and films are powerful ideological tools that work in consort with each other.”

If maps impose a two-dimensional order on a disorderly space, Moullet is genuinely interested in the cuts in the urban fabric, the gaps and disconnections, in the unesthetic and heterogeneous, eclectic and incongruent. His cartographies are composed of unconventional signs, amusing billboards, unorthodox posters, banal parking lots and myriad unexpected urban and architectural configurations resulting from public policies and the pervasive modernization. The travelogue-style voice-over narration, whether appealing and official (Didier Beaudet in Foix) or nasal and slightly cheeky (Moullet in Le Ventre de l’Amérique), duplicates the visible or deliberately and ironically diverges from the image. In Foix, “everything is tailor-made for young people,” who must pass through a hospital parking lot on their way to school, and the cultural center – built in front of a prison – also serves as a bus station. Foix is “the only French town where you can park on a bridge,” a singularity that resonates with Des Moines, where “there isn’t much traffic, but there are four bridges side by side.”

It would be extremely reductive to describe Moullet as a mere flâneur, since most of these films are motivated by the economic transformation of Western societies. The spoil tips are a relic of a mining era (La cabale des oursins); the dog equipment sales in France surpass Senegal's GDP (L'empire de Médor); only cargo trains traverse Des Moines where the consumer society prospers (shopping malls, Christmas euphoria). To exhaust all the aspects of a topic (Keller and Cavé 2009), Moullet frequently refers to statistical data (100 000 visitors of the Foix Castle; 20 tons of dog waste; 2000 francs for the annual dog food) and elaborates typologies (of spoil tips or dog waste). As Damien Keller and Frédéric Cavé (2011, 7) argue, the ambiguity of the méthode Moullet is reflected in the gap between the minimal budgets of his films and their examination of the “macroscopic manifestations of production systems.”

However modest his budgets, Moullet has worked within a relatively stable French funding system, often receiving support from the national film centre CNC. He has also navigated between private and public funding, and many of these shorts were supported by both the CNC and the private TV channel Canal+ (three of them were made for the experimental TV show L’Œil du Cyclone, see Alcalde 2019). Yet, the provenance of the funding, the budgetary constraints, and the (short) television format did little to modify Moullet’s filmic practice. If anything, they have prompted him to seek ever more imaginative solutions for his joyful critiques.